September 11 , 2019

Even As a $15 Wage Floor Kicks In, Big Apple Eateries Flourish

By James Parrott

In July, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the first increase in the federal minimum wage in 10 years. While that bill's fate in the Senate is doubtful, the House approval has given renewed attention to the question: What has been the economic effects in the cities and states where higher minimum wages are already being phased in? New York is one of those cities, with a $15-an-hour minimum wage now in effect for employers with more than 10 employees.

With the highest proportion (80 percent) of low-wage workers in any industry, the city’s restaurants are Exhibit A for understanding the impact of this rising minimum wage on jobs, workers, and businesses. For the past few years, groups claiming to speak for New York City restaurants have told the media that the higher minimum wage was forcing restaurants to hire fewer workers, or even close their doors. A new report that I co-authored with my Center for New York City Affairs colleague Lina Moe and Yannet Lathrop of the National Employment Law Project used the best available and most up-to-date government data to examine such claims. We found they did not hold up to close scrutiny.

Until the last day of 2013, New York State’s minimum wage was the same $7.25 an hour as the federal minimum wage. Since then, the State minimum wage for large New York City employers and all fast-food workers has risen in stages to the $15.00 an hour that took effect on the last day of 2018 day of 2018. (The wage floor will rise to $15 for small employers at the end of this year.) During these years, the cash wage restaurant owners are required to pay tipped workers (who account for about half of full-service restaurant employees) also doubled, from $5 to $10 an hour.

Key findings of our report, based on data from the entire 2013-18 period, included:

The number of jobs in New York City full-service restaurants (where wait staff serve customers at tables) rose 17 percent from 2013-18, and the number of jobs in limited-service restaurants (where customers order food at counters) grew by 27 percent. Total restaurant employment grew 35 percent faster than the city’s total private sector job growth from 2013-18.

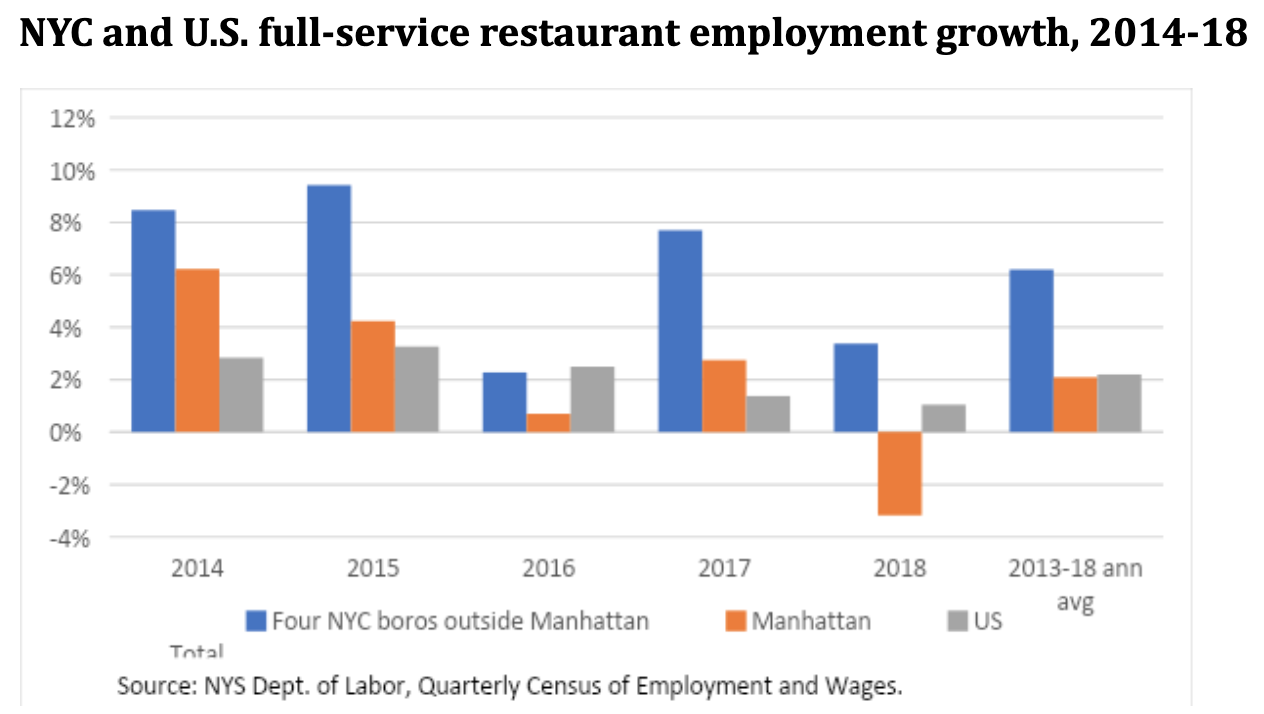

By every measure that we examined (jobs, number of restaurants, and average wages) New York City restaurants fared at least as well as the national averages in this industry in each of those categories over this period of sharp minimum wage growth locally.

Compared to 12 large cities around the country that did not have any minimum wage increases from 2013-18, New York City restaurants had stronger job growth and much greater average wage growth.

New York’s rising minimum wage has tremendously benefited low-wage workers, including those employed in both full-service and limited-service restaurants.

New York City workers in the lowest-paid three deciles of the wage distribution have seen inflation-adjusted wage gains of 8.5 to 15 percent since 2013 (the largest wage gains for these workers in the last 50 years). Wage gains among restaurant workers have been even stronger, with 2013-18 real wage increases averaging 15-23 percent for full-service and 26-30 percent for limited-service restaurant workers.

The restaurant industry’s strong, sustained growth also argues for ending New York’s current subminimum wage for tipped workers. The State now permits restaurant owners to pay tipped workers a lower cash wage than the overall State minimum wage, provided that tips received bring the total earnings for each worker to the statutory minimum wage level.

Seven states, among them California, Minnesota, Oregon, and Washington, instead require restaurants and other employers of tipped workers to pay the State minimum wage without factoring in tips. Restaurants in these states have been thriving; there is no evidence that the absence of a lower tipped-credit wage harms the industry or lessens tips for affected workers. Moreover, other compelling research shows that New York State should end the subminimum wage for tipped workers here, because they are more vulnerable to sexual harassment and wage theft and suffer higher rates of poverty and hardship than those in states where the subminimum wage has been eliminated.

The new report should lead reporters to more carefully assess claims made by restaurant representatives regarding the impact of minimum wage increases. Here’s what long-time Crain’s New York Business columnist Greg David recently concluded:

Interview restaurant owners and they say $15 for tipped workers will put them out of business. Some say they have already laid off staff, cut hours and delayed expansion plans. However, when I press for details on the layoffs and the reduction in hours, or ask to talk to the staff, suddenly I don’t get good answers. I have decided what’s important is not what business owners say but what they do. The numbers say few have followed through on those threats.

No question, New York City restaurants face genuine economic headwinds. There has been a steady rise in real estate prices and rents in restaurant-heavy Manhattan. The strong U.S. dollar has eroded the purchasing power of the foreign tourists so important to the industry overall. And increasingly popular third-party delivery services charge restaurants high commission fees, eating into profits and likely reducing direct restaurant employment, as also happens when eateries turn to temp workers to keep up with demand in a tighter labor market. But this is an industry constantly buffeted by changing circumstances and consumer preferences. Locally owned restaurants in particular must continuously respond to such trends to maintain their appeal to customers.

Some factors affect all restaurants similarly but still require each restaurant to successfully adapt. The evidence is that most New York City restaurants have effectively adapted to the rise to $15 in the local minimum wage. And the over-arching lesson is that businesses can and will adapt even as low-wage workers see historic increases in their earnings.