What Makes Manhattan’s Koreatown A New Type of Ethnic Enclave?

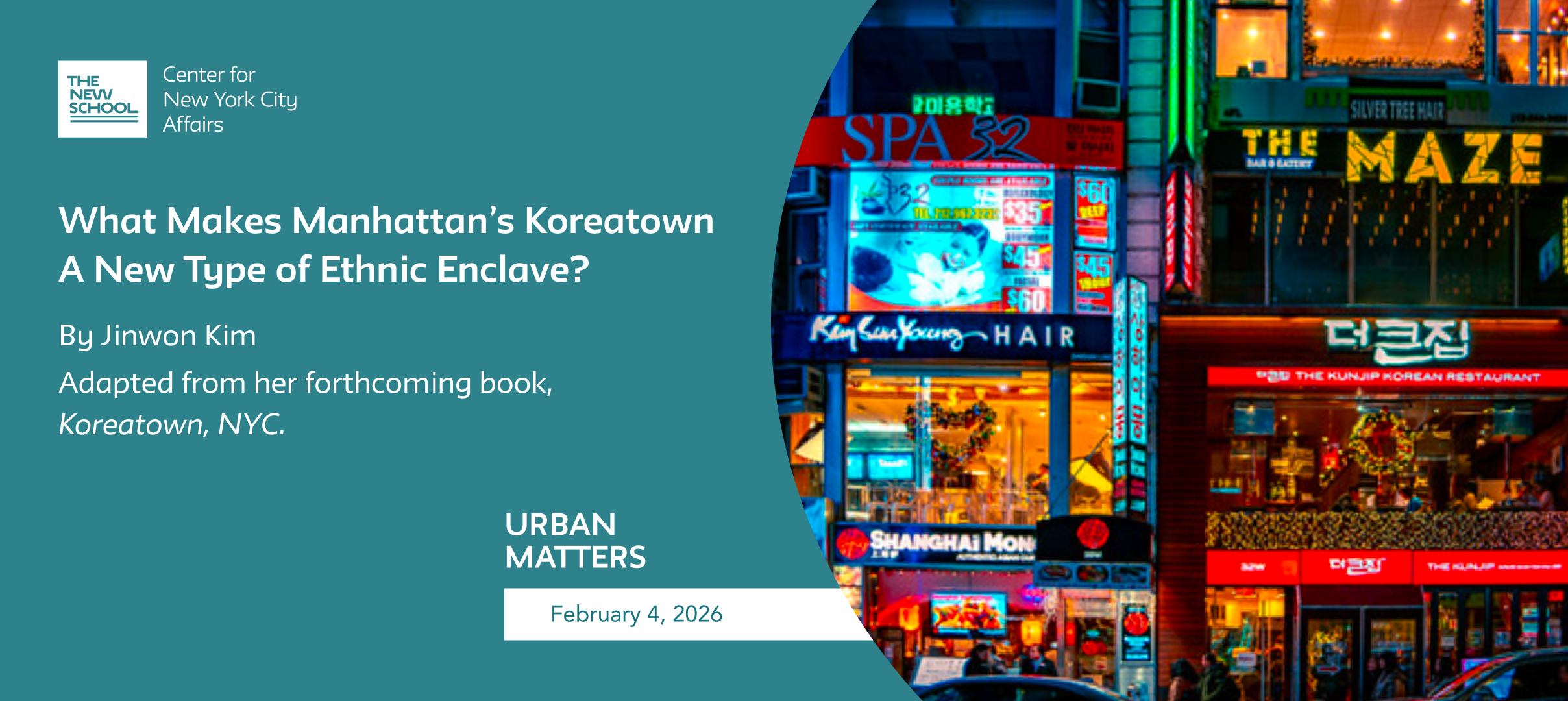

Koreatown was once ‘hidden’ or ‘shadowed’ by adjacent New York icons such as the Empire State Building, Herald Square, Penn Station, and the flagship Macy’s. But today, it is known as the home for a taste of Korea for both ethnic Koreans and non-Korean New Yorkers, where restaurants, bars, noraebang (karaoke bars), internet cafés, and all-night spas offer ‘Seoul-style’ consumption.

This visibility comes with the growing popularity of breakout stars like the K-pop group BTS as well as pop culture products, including Korean dramas and movies, such as Squid Game and Parasite, respectively.

One solitary block of Manhattan’s West 32nd Street between Broadway and Fifth Avenue is officially called Korea Way, but it is usually referred to by its nickname, Koreatown or K-town. That term also applies to a space extending to some parts of 35th Street, Sixth Avenue, and Park Avenue.

At first glance this area appears to be an ethnic enclave, where members of an ethnic group share their unique culture, values, beliefs, and lifestyles. It once offered food and services for Koreans who had immigrated after the liberalized Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. During the 1970s and 80s, the majority of these Korean immigrants owned businesses or worked in the nearby Korean Business District, a rectangular area from 24th to 34th Streets between Fifth and Sixth Avenues, home to Korean wholesalers. At the time, very few non-Koreans could be seen in the area.

But things have changed drastically. Koreatown now contains a cluster of homeland-style businesses such as Korean restaurants, bars with Korean-style food, a food court, Korean franchise bakery-cafés, Korean brand cosmetic stores, Korean hair salons, and noraebang, representing Korean ethnic identity via shared lifestyle and consumer culture.

Korea’s ‘nation branding’ strategy, new patterns in Korean migration, changes in the sociocultural and urban landscape both in South Korea and in the United States, and shifts in tourism and urban policies in New York City have shaped the development of Manhattan’s Koreatown into a new type of ethnic enclave. I call it a ‘transclave,’ a commercialized ethnic space that exists exclusively for consumption, leisure, and entertainment where transnational consumer culture from a sending country is embedded within a physical space in a receiving society.

This particular transclave becomes a cultural platform for the Korean government and relatively small-to-medium-sized Korean corporations to market the nation and its brands for both economic and political benefit, cultivating it as an entertainment space with the intention of nation branding and promoting Korean culture and products overseas. Korea’s cultural policies demonstrate the growing importance of nations’ 'soft power' and 'cultural wealth' in the current era of global competition. Korea has actively participated in new global trends by adapting national cultural products for overseas consumers and consumer culture.

The financial crisis of 1997 was a critical moment for the Korean government, as new economic and sociocultural policies and strategies were introduced to overcome financial uncertainties. I argue that the government, rather than stepping in as the main actor, took the role of facilitator for the new global order in implementing International Monetary Fund policies. In addition, the Korean government actively collaborated with various economic actors – in this case Korean corporations – in order to bring new revenues and to overcome the financial crisis through business strategies as part of its broader nation branding plan.

Soft power becomes a marketing tool for the nation and reinforces the idea that the nation can be a brand that targets a wider audience. New York City is one of the most critical global markets in nation branding projects, and the landscape of Koreatown in Manhattan reflects the flow of new cultural and economic investment. Because cultural products from a sending country are often placed in traditional ethnic enclaves, the new branding policies mobilize different types of business owners to create a new type of ethnic space.

As a transclave, Koreatown serves as an intersection at which Korea’s political, economic, social, and cultural influences meet New York City’s diverse cultural mosaic. As with a traditional ethnic enclave, ethnicity enters the marketplace to become commodified in a small section of New York City. Koreatown consists primarily of small- and medium-sized commercial and office buildings, as well as a handful of manufacturing buildings left over from the area’s history as a garment district. This small block, however, has unique traits that differentiate it from other ethnic enclaves, particularly the typical Chinatown model.

First and foremost, Koreatown exists only for consumption and has rarely served any residential purpose. Koreatown is zoned as a commercial district by the New York City Department of City Planning, which allows Koreatown to be open for business at all hours. Furthermore, investors in Koreatown tend to open restaurants and bars not only on the first floor of buildings, but also on the second, third, and fourth floors; this is a common practice in Seoul, but atypical of New York City business spaces. As such, Manhattan’s Koreatown has a higher concentration of stores than do other consumption spaces in New York City, which endows the space with a plethora of shopping, eating, and entertainment opportunities.

Second, Koreatown in Manhattan is a space for 'consuming ethnicity.' Americans expect Koreatown to be like other ethnic enclaves, such as various Chinatowns, Little Italys, and Little Indias in New York and in other metropolitan areas. Koreatown shares common elements with these other ethnic enclaves but is also unique. I locate Koreatown in the rise and fall of ethnic enclaves in urban America and their transition from a space of isolation to a space for residence or work, and, finally, to a new iteration of a space for entertainment, leisure, and consumption. Indulging in and having knowledge about ethnic foods is one of the most common and popular ways for city dwellers to demonstrate their understanding and appreciation of diversity and multiculturalism; it is also important in establishing a cosmopolitan identity.

For many consumers – particularly non-Koreans – Koreatown is a commercialized space where one can seek out and be immersed in an authentic experience: a transnational culture embedded in New York City’s diverse racial and ethnic mosaic. In fact, Koreatown in Manhattan is a space where a sending state’s socioeconomic strategies and policies are negotiated with the ethnic community and shape the cityscape in urban America.

Jinwon Kim is an assistant professor of sociology at Smith College and the author of Koreatown, NYC: The Consumption of a Transnational Brand, which will be published by New York University Press in May, 2026. This lightly edited adaptation excerpted from its introduction appears here with the permission of the author and publisher.

Photo by: Artem