BANNED for 28 Years: How Child Welfare Accusations Keep Women out of the Workforce

By Abigail Kramer | February 2019

Francine Almash was not especially surprised when an investigator from New York City’s child welfare agency showed up at her door. A few months earlier, her then-10-year-old son, Shawn, who is autistic, had been pinned to a wall by a crisis counselor in his special education classroom and come home with a broken thumb. Almash refused to send him back, and so the school called the State’s child abuse hotline to report her for neglecting Shawn’s education.

What shocked Almash was not the phone call—which she saw as retribution for criticizing the school—or even the ensuing investigation, which she was able to counter with proof that Shawn was being homeschooled.

The stunning part was what came next: Shortly after her case was closed, Almash received a letter informing her that her name had been added to a registry of people investigated for child abuse or neglect. Though she’d never been proved guilty—or even had her case heard by a judge—the record would last until her youngest child turned 28 years old, and it would show up on background checks for any number of jobs where she might come into contact with children or other vulnerable people.

In addition to raising three boys on her own, Almash had just spent two years working toward a degree in education. With a child welfare record, she says, “I’d be shut out of any job at a school.”

While she didn’t know it, Almash was far from alone. Nearly every state in the country keeps a centralized database of child welfare investigations, though rules vary by state about whose records are made public and for how long.

On its face, the goal is unassailable: to keep abusers away from potential victims. But critics say the registries are much too long and easy to land on—especially for low-income women of color, who are subject to far more than their share of child welfare investigations.

The vast majority of people on New York's registry got there because they were accused of some form of neglect, such as inadequate food or housing, rather than abuse. Most never had a child removed from their home, or even appeared in court. Many have no idea that they have a case on record unless they're turned down for a job. And while there is an appeals process, lawyers for parents in the child welfare system say that it is limited and obscure, and most people never learn that it exists.

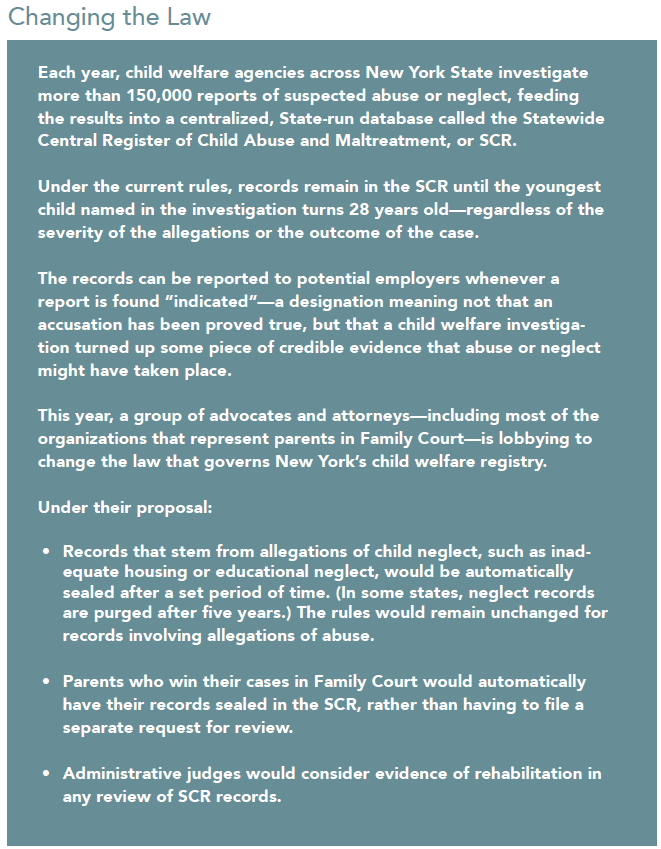

“We have this bizarre system where you can be on the registry for things like your teenager missing school, and it will stay on your record for far longer than a felony conviction for assault,” says Chris Gottlieb, who is the co-director of the Family Defense Clinic at New York University School of Law, and who is working with other attorneys and advocates to rewrite the law that governs New York's registry.

Under the State's current rules, records are reported to potential employers any time a case is found "indicated"—a designation meaning not that a person is guilty, but that an investigation turned up some piece of credible evidence that abuse or neglect might have taken place. That evidence may be outweighed by other findings; the case may have been closed without further action. Nevertheless, the record is made available to thousands of employers that hold government contracts to work with children, the elderly, or people with disabilities.

Some jobs that require a registry check are those you might immediately guess: teachers, for example, or daycare workers. Others are less self-evident, including substance abuse counselors, crossing guards, home health aides, people who deliver supplies to nursing homes, drivers for the disabled, and most jobs in a hospital. An indicated record can stop a parent from volunteering at her child’s school, or prevent a grandmother from becoming a foster parent to her grandchild.

New York State doesn't report the total number of people listed as having indicated cases in its child welfare registry, but available data suggest that the figure is large: In 2017, Almash's investigation was one of nearly 50,000 resulting in indicated cases across the state, according to the Office of Children and Family Services (OCFS). That year, the agency received more than 300,000 requests for database clearance checks.

The cumulative result is “a system that targets poor women, then shuts them out of jobs so they stay in poverty,” says Joyce McMillan, a longtime advocate for parents with child welfare cases in New York City who launched the current effort to change the register law.

To Almash, the entire experience with child welfare seemed designed to punish her for a crime she hadn't committed.

Case notes from her investigation show that shortly after pulling Shawn out of school, Almash submitted a homeschooling plan to the city’s Department of Education and enrolled Shawn in multiple classes and programs for homeschooled kids.

Still, the investigation went on for 60 days. Caseworkers showed up unannounced at Almash’s apartment, taking notes about the contents of her refrigerator and the cleanliness of her bedroom, inspecting her sons’ bodies for bruises, and interviewing neighbors, family friends, the kids’ doctor, and Shawn’s therapist—all of whom had uniformly good things to say about Almash’s parenting, according to the caseworkers’ notes. They visited Shawn's brothers’ schools. The boys were taken into separate rooms and questioned, repeatedly, about their mother.

The ordeal was so stressful that Shawn and his brothers would turn out the lights and hide when a caseworker knocked on the door, Almash says. “They did not feel safe with her around."

With help from a lawyer, Almash was able to file an appeal with the State and get her child welfare record expunged—an option that's not realistic for most people who end up on the registry, says Gottlieb.

Many people never learn that it’s possible to have their records be reviewed, Gottlieb says. Even when they do, there is no right to an attorney in the appeals process, and most people can't afford to hire a lawyer on their own. "We often go to these hearings," Gottlieb says, "and not a single other parent there will have representation."

***

Advocates frequently make the case that living under the watch of the child welfare system causes harm to low-income women of color in much the same way that over-policing hurts black and Latino men. There is a similar experience of surveillance, they argue, and—for those who come under scrutiny—the same presumption of criminality and bad intent.

Much like arrests and incarcerations, child welfare investigations plot an uneven map: extremely rare in middle-class and wealthy neighborhoods, where parents tend to use private resources to deal with family problems like a drug addiction or a chronically truant teenager; much more common in low-income areas, where those problems often thrust families under the scrutiny of public institutions.

In 2017, for example, New York City, which runs by far the state’s largest child welfare agency, conducted nearly 1,800 investigations in the high-poverty, mostly black and Latino community district that includes Brownsville, Brooklyn, according to data published by the City’s Administration for Children’s Services (ACS).

Just a few miles away, in the much wealthier, whiter community district that includes the neighborhood of Forest Hills—and which is home to approximately the same number of children as live in Brownsville—ACS conducted just 250 investigations. Citywide, more than 90 percent of kids who end up in foster care are black or Latino, according to an annual report by the Citizens’ Committee for Children.

In recent years, several cities and states have passed laws designed to shrink the obstacles that keep people with criminal records out of the workforce. New York City’s Fair Chance Act, for example, makes it illegal for employers to ask about an applicant’s criminal history until after they’ve made at least a conditional job offer.

But advocates say that, in some ways, it can be even harder to muster public support for women accused of being bad mothers than for people coming home from prison.

Don Lash is the executive director of Sinergia, a New York City organization that, among other programs, hires staff to work in the homes of people with disabilities, helping with chores like cooking and running errands. It’s a low-wage, high-turnover field, and applicants are, for the most part, women without much formal education.

Their background checks frequently reveal child welfare cases, Lash says, but he receives no information about what the allegations were or whether they were ever proved. “If there’s a criminal case, you get notice of what the charge is, so you can exercise discretion. When they tell me that 10 years ago someone jumped a turnstile or had a marijuana charge, I can say I don’t care.”

With a child welfare case, Lash says, he usually can’t take the same risk—even on someone he’d otherwise like to hire.

“If you’re shut out of jobs in our system,” Lash says, “you’re also shut out of schools, daycares, working with the elderly. What other jobs are there in some communities?”

***

Cathy Wright has spent nearly two decades making up for past mistakes.

Near the end of high school, Wright learned how bad decisions can gain their own momentum, careening her down an unexpectedly short and slippery slope that started with a drug-dealing boyfriend and dead-ended in an addiction to crack-cocaine and a 15-month stay in New York City’s Rikers Island jail.

Her two sons, just 1 and 2 years old at the time, were placed by the City’s foster care system with their aunt.

When she came out of jail, Wright entered a recovery program and won back custody of her boys, bringing them first to a homeless shelter, then to the Brooklyn apartment where they still live. She earned money by babysitting other people’s kids and she stayed out of trouble with child welfare and the law. Last year, her older son became the first person in his family to graduate from college—an accomplishment that inspired Wright to sign up for night school and earn her GED, followed by two certificates in medical administration.

But when she began looking for jobs, Wright was shocked to learn that she will remain on New York’s child welfare registry for another seven years, which almost certainly precludes her from working at a hospital.

"I did a bad thing, but I'm not a bad person," Wright says. “The stigma shouldn’t last this long when you’re trying to improve yourself and do better."

Wright would like to appeal to have her record sealed, but the process is daunting and convoluted, and her chances of winning are poor.

By law, people with indicated cases in New York State’s register have two opportunities to request that their records be amended or sealed: First, immediately after a child welfare investigation, within 90 days of being informed of its outcome; and second, within 90 days of a background check submitted by a potential employer.

The 90-day time limit is a major hurdle for people seeking to amend their records, says Kylee Sunderlin, an attorney with Brooklyn Defender Services. While OCFS is supposed to send a letter informing people of their right to a review, many people never receive it—a problem that’s exacerbated by the fact that so many of the subjects of child welfare investigations live in temporary housing.

When they do get the letter, people often don’t know how to interpret it without help from a lawyer, Sunderlin says. “If they don’t have someone helping them, they just get a letter saying they’re time-barred. So, understandably, a lot of people give up.”

In 2017, the State received fewer than 9,300 requests for what’s known as an “administrative review”—the first step to having a record expunged or sealed, according to OCFS data.

Even if Wright were able to overcome the bureaucratic barriers and move forward with a hearing, her accomplishments over the past two decades would be rendered meaningless. Due to a vagary of the law, the administrative judges who review child welfare records are able to consider evidence of rehabilitation only if a review is requested in the first 90-day window, immediately after a child welfare investigation. In those cases, a judge can decide to uphold the indicated record but seal it from background checks by employers, on the grounds that the indicated report is no longer relevant to working with children.

If the request is made during the second window, however—when the subject is applying for a job, often years after their investigation—the judge cannot consider anything other than whether the original allegation was likely true.

“It’s hard to see how anyone could think that makes sense,” says Gottlieb, the New York University attorney. “You might have someone who’s been sober for 10 years and wants to work at an organization where she could help other people in recovery. But a judge is not permitted to even consider her track record of rehabilitation.”

In the bill proposed by Gottlieb and other advocates, judges would consider evidence of rehabilitation in all reviews.

With a new, more left-leaning State Legislature, advocates are optimistic about the possibility of finding sponsors and reforming the law in the coming year. “The goal was to draft a bill that is not controversial—one that simply allows the law to better accomplish what it was originally intended to accomplish,” Gottlieb says. “It’s one step at a time, but we’re trying to make a more rational system.”