Nearly Two-Thirds of New Yorkers Can’t Make Ends Meet. Here’s a Gameplan for Turning that Around.

In 2023, FPWA and the Community Service Society launched the National True Cost of Living Coalition, and commissioned the Urban Institute to develop the first national True Cost of Economic Security (TCES) measure.

Today we have a TCES that defines economic security as having the resources to meet a comprehensive set of regular household costs, set aside savings for future planning and short-term emergencies, and manage debt.

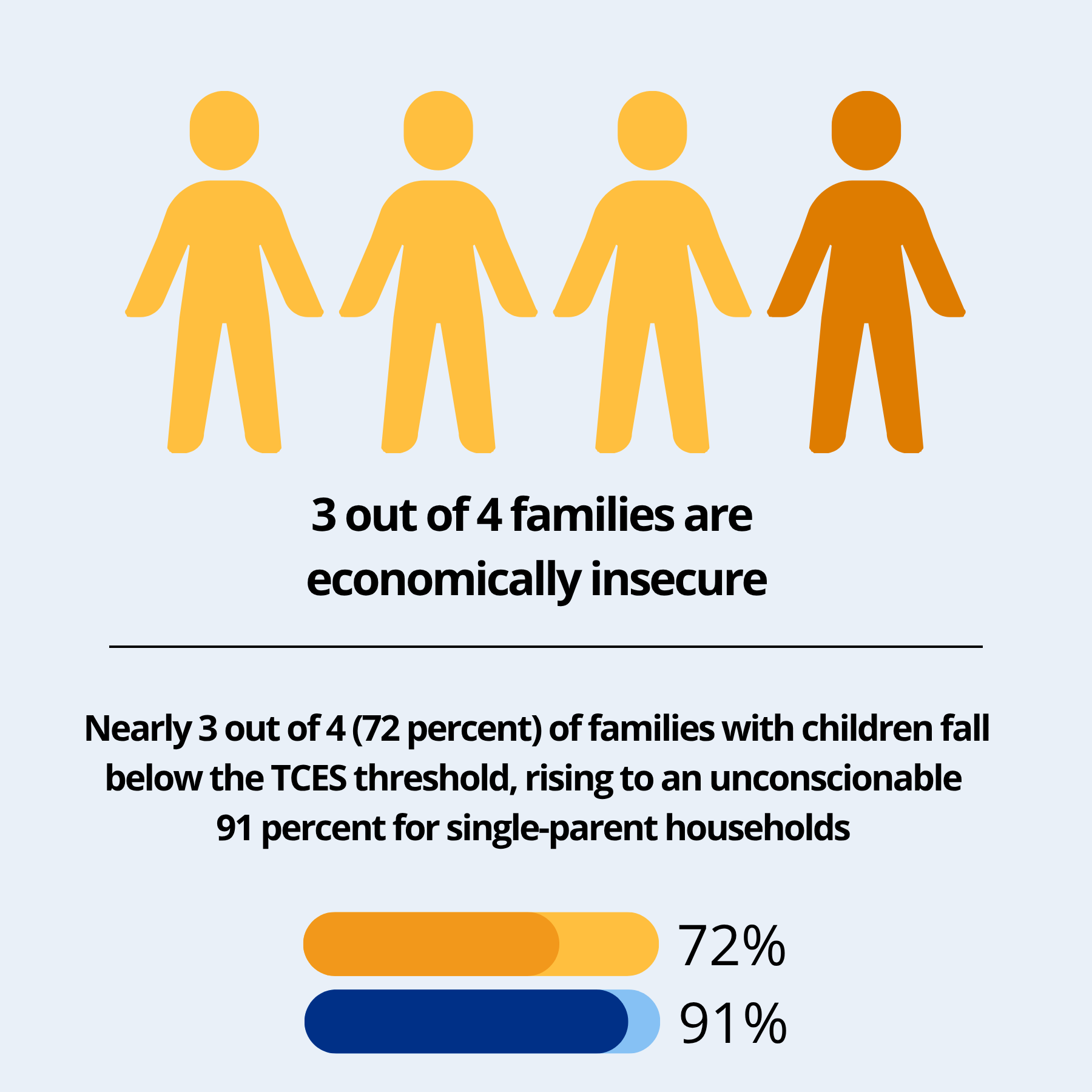

Using TCES, we now know that a staggering 62 percent of New Yorkers are economically insecure.

On average, New York City households below the TCES threshold would need an additional $40,600 a year to be economically secure. For families with children, that gap grows to $52,600. Simply put, economically insecure New York City households are tens of thousands of dollars away from true security.

The scope and implications of these findings are laid out in a new FPWA report, “True Cost of Economic Security,” and will be presented in detail at an event at The New School on Nov. 14.

For the many millions of economically insecure New Yorkers, piecemeal policy changes will not be enough to improve their circumstances. Comprehensive responses are needed in four major areas.

The first is increasing the scarce resources available to families living below the TCES threshold.

Recent wage growth among low- and middle-wage earners nationally was not matched here. To the contrary: New York City low- and medium-wage workers experienced real wage loss of 2.8 percent and 2.4 percent, respectively, between 2019 and 2023.

The minimum wage in New York City ($16.50/hour) annualizes to approximately $34,320. However, a single-person household with no children would need double that to live with economic security here.

Even those working above the minimum wage are locked out of economic security. The City must explore policies that will raise wages for both low- and middle-income earners. TCES data provides key information for such fair wage setting.

For openers, the sub-minimum wage for tipped workers and workers with disabilities must be eliminated. The City should also explore options to support raising wages for workers making above the minimum wage. That may include tax incentives for providing wages that support economic security and disincentives for failing to do so. The City may also wish to explore its procurement powers to incentivize family-sustaining wages.

Federal, state, and municipal legislation using TCES as a guidepost, and as a prevailing wage in certain industries, would likely prove highly effective in dismantling structural and systemic wage deprivation.

The City and State should use TCES data to study labor market inequities, and identify occupations with a disproportionate share of economically insecure households. Such analysis would be critical to increasing wages in such sectors as health and human services.

The federal government’s Official Poverty Measure (OPM) is, perversely, a highly effective tool for maintaining wage deprivation. The OPM for households of two adults and two children is $32,150.

At New York City’s minimum wage, this same family would earn approximately $68,640. Despite being well over the OPM, and therefore ineligible for most income support programs, these families fall far short of economic security. In fact, that’s all too often true for families earning up to twice that amount.

The City and State should explore expanding eligibility for income support programs using the TCES as a guide.

TCES can also inform asset limit thresholds for public assistance programs. Asset limits prohibit people receiving income supports from saving even a small amount for emergencies. And individuals with even a modest amount of savings are frequently unable to access critical programs. These restrictions trap families in a cycle of economic insecurity.

Three years ago, New York State increased the amount of assets public assistance applicants can have from $2,000 to $2,500 (and from $3,000 to $3,750 for households where any member is age 60 or older). But these changes do not go far enough.

New York lawmakers should also revisit targeting and expanding the Working Families Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit, especially given the significantly higher cost of living for households with children.

Secondly, reducing costs is as important as increasing resources. That includes the costs of:

Housing. For New York City families falling under the threshold of economic security, housing costs consume a daunting 45 percent of their annual resources.

Both demand-side solutions – such as increased, wider-reaching housing subsidy programs – and supply-side solutions – such as increased social, public, and income-targeted development – would benefit from a TCES analysis. Policymakers can score the effects of proposed policies against the TCES measure of economic security.

Child-rearing. In every New York City borough, households with children have higher costs. Because most do not have equal resources, they consequently have higher rates of economic insecurity.

Using a TCES analysis, the City could fully fund childcare programs, afterschool, and pre-K for all three- and four-year-olds on a sliding scale. Targeting families at the lowest end of the TCES scale and gradually expanding upward would ensure that limited resources reach the families most in need.

Healthcare. It’s the second-largest cost for households with children, and one that many families will be feeling more acutely because of impending federal cuts in Medicaid.

Over 70 percent of New York City public hospital patients rely on Medicaid or have no insurance. With fewer Medicaid patients, less government funding, and lower payment rates, H+H Hospitals, which already operate under narrow margins, will be at risk of closure and reduced services. The City may need to increase funding to fill gaps and ensure public hospitals stay open, particularly for economically insecure families.

Taxes. By utilizing TCES, policymakers can ensure that tax policy doesn’t exacerbate economic insecurity and that tax cuts and refundable tax credits go to those who need them most.

Third, we need new efforts to help economically distressed New Yorkers build essential savings.

Tax-privileged retirement accounts such as 401(k), 403(b), and IRA plans help build savings and reduce tax burdens, especially when they offer employer contributions. Yet higher-income families are 10 times more likely to have such accounts than low-income families.

New income support and refundable tax credits could help pave the way for programs such as a guaranteed basic income structured on a sliding scale using TCES thresholds.

One bold solution offered to support wealth-building is “baby bonds”: publicly funded trust accounts provided to all children at birth and progressively funded. Accessible at young adulthood, baby bonds offer “start-up capital” to invest in wealth-building opportunities such as education, homeownership, or entrepreneurship.

Baby bonds and guaranteed income programs are ways government can reimagine the tax code to provide individuals and families with sufficient income and capital to invest in their futures.

Fourth, TCES data must be used to identify geographic areas that require targeted policy responses.

For example, the data paints an upsetting picture of household finances in the Bronx, where 78 percent of all families and 88 percent of households with children are economically insecure. The City and State must explore place-based policies to support these households – recognizing historical practices of discrimination, environmental degradation, and disinvestment. Place-based solutions could take several shapes; all must be focused on improving the lives of those most in need.

In sum, TCES findings pose an essential question: Is New York City a place where anyone who’s born or moves here can thrive? Or will that be so just for beneficiaries of intergenerational wealth?

Since 1922, FPWA has been a leading anti-poverty, social policy, and advocacy organization in New York City. The lead analysts for the report from which this Urban Matters is adapted were Brad Martin, former FPWA senior fiscal policy analyst, and Jared Launius, FPWA campaign manager of the True Cost of Living project.

Photo: birdlives9.

Graphics: Courtesy of FPWA.